What happens to us in our youth impacts the rest of our lives. Sorting that out later in life sets us on a hero’s journey.

***

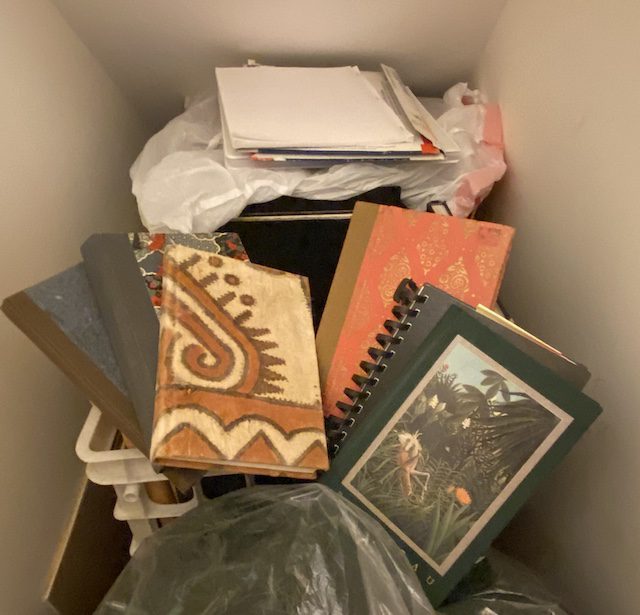

I found the journals while cleaning closets during spring break. Six 9-by-6-inch books written by my new husband’s daughter, who had taken her life at age 24. A person I’d never met. When I asked Keith about them, he said Gretchen had told him she wanted to tell herself the truth, so he’d encouraged her to keep a journal. I nodded then asked for permission to read them. “Oh yes,” he said, “reading Gretchen’s journals is the best way to get to know my daughter. And you can ask me anything you’d like.” Keith didn’t speak about Gretchen much but enjoyed talking about her when he did. Of course, I was curious.

On the first morning of my next break—our 4th of July vacation—I stacked the six books in chronological order and dipped into each, one after another. I quickly discovered that although Gretchen had written for herself, she expected to have readers. But, as I read along, her honest admissions and sexual pleasure-seeking brought out the worst in me— judgment, jealousy, anger—qualities I worked hard to hide. I abandoned one book then another and another. When Gretchen described an unsuccessful suicide attempt in her final book, a flashback to the childhood nightmare I hadn’t had in years spiraled me into a panic. I closed the book and packed up the journals. This was more than I’d bargained for.

And yet, knowing my relationship with Keith would be less if I distanced myself from his loss, I made a firm promise to read the journals, all six books, every word from beginning to end, after I resigned my long-commute job the following year. Keith and I were building a house together, and I would oversee the project.

While house building and reading the journals that following year, I decided to write about Gretchen and include some reflections inspired by her words—about her, but not a biography; just Keith’s Gretchen stories and her journal entries. Certainly not those thoughts or feelings I worked hard to hide. For several months, I wrote Keith’s stories and transcribed journal entries, which I wove into a chronological draft of a possible book. Strangely, my own stories seeped through the pages.

A year later, as the house neared completion, I signed up for a creative writing class to learn how to polish the manuscript for publication. I was a seasoned academic and technical writer, only rarely creative or literary. One night in class, I read a selection about five-year-old Gretchen, whose childhood world ended when her parents divorced. The passage included hints about the violent crime that happened to my family when I was five. “Who is the protagonist?” a classmate asked. “What is the plot, the conflict, the story arc?” Questions continued. “Why did you write this? What is the story really about?” I didn’t know. But, after no small amount of weepy, head-bowed, shoelace-fixated self-pity, I determined to find out. To close the distance and face the fearful feelings I’d fled from the first time I read her journals.

Based on the connections—the inexplicable disruptions when we were both just five years old, depression and anxiety episodes starting for both of us at sixteen, similar troubles in college and rejection in love—I created a braided narrative, alternately appropriating Gretchen’s journal entries and Keith’s stories in one chapter then telling my same-age stories in the next. For my chapters, I drew from thirty years of letters I’d written to my parents, which my mother had kept, and my sisters sent to me after clearing Mother’s attic in advance of her eventual move to a care facility. At the time, I hid the bags of letters in my closet, hoping to forget my unstable past, which appeared in the letters despite my curated prose. Now, I needed to bring that past to light. Yet all along, I hoped I could reveal my personal secrets without returning to the emotional pain and suffering.

As for the alternate chapters, I wondered if I could rightfully use someone else’s stories and still write an honest memoir. Memoirists write about all sorts of relationships: mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, spouses, friends, and lovers. So, in a sense, I reasoned, we creative nonfiction writers all appropriate others’ stories to tell our own. Telling one’s truth is the heart of memoir, but what about writing about someone you never met? I thought of Julie Anne Powell’s 2005 blog turned memoir Julie & Julia: 365 Days, 524 Recipes, 1 Tiny Apartment Kitchen. A gimmick, some critics said, a stunt according to Julia Child, the Julia in the title. Not at all what I wanted to do, though arguably very like the first draft of my “book.” Looking back, I can see the problem: I was not yet ready to let go of safety, comfort, and certainty to tell a real story.

Next week, Part II of this essay, which was published in Cleaver Magazine’s August 22, 2024 Craft section: https://www.cleavermagazine.com/writing-a-memoir-partly-about-a-person-i-never-met-a-craft-essay-by-carole-duff/

Linkup with Five Minute Friday: https://fiveminutefriday.com/2024/09/05/fmf-writing-prompt-link-up-youth/

it’s hard sometimes isn’t it? To be truthful enough with ourselves to tell the truth to others. FMF11

Yes, indeed, the hardest is telling the truth to ourselves, at least it is for me. Thank you for your encouragement! -C.D.