One afternoon about ten years ago when I was visiting my mother at her home in Connecticut, we decided to do a little “spring cleaning” in the kitchen. Mother sat at the table and sipped a cup of decaf while I explored. Memories poured from each cabinet and drawer. I ran my fingers over iron skillets, the yellow tin flour bin, and my father’s favorite cereal bowl.

Then I opened the base cabinet drawer and noticed short pieces of string piled in the front left corner. “What’s this?” I asked, holding up a handful of string.

“Oh, my mother used to keep bits of string,” Mother said.

“They’re too short to be of any use,” I said.

“Just leave them there,” she said. Memories. I returned the string and closed the drawer.

In 1960, poet Donald Hall published a memoir about summers spent with his grandparents on their farm. He opened with this story: “A man was cleaning the attic of an old house in New England and he found a box which was full of tiny pieces of string. On the lid of the box there was an inscription in an old hand: String Too Short To Be Saved.” Thus, Hall titled the recollections of his grandfather’s stories.

During “The Long Day,” Hall and his grandfather did chores in the morning and hayed a neighbor’s field in the afternoon. They were tired on the way home with the last load, and Hall was hungry. Bumping down a hill, an iron rim fell off one of the wheels. Hall and his grandfather managed to fit the rim back onto the wooden wheel, but as they made their way home, Hall kept looking at the rim and thinking about how hungry he was.

Hall’s grandfather chuckled. “Did I ever tell you about how Mark Bachelor proposed to his wife,” he said, referring to Hall’s great-great-great grandfather on his mother’s side. “Mark didn’t talk much,” Hall’s grandfather continued. “He knew a girl from church and he used to walk home with her but he never knew what to say. Come time he wanted to marry her, but he didn’t know how to ask. He rode up to her one day, when she was in front of her house, and pointed to behind his saddle and said, ‘on or off?’”

Hall and his grandfather laughed. “I guess she must have climbed up then and there,” Hall’s grandfather said, “or there wouldn’t have been any more Bachelors around here.”

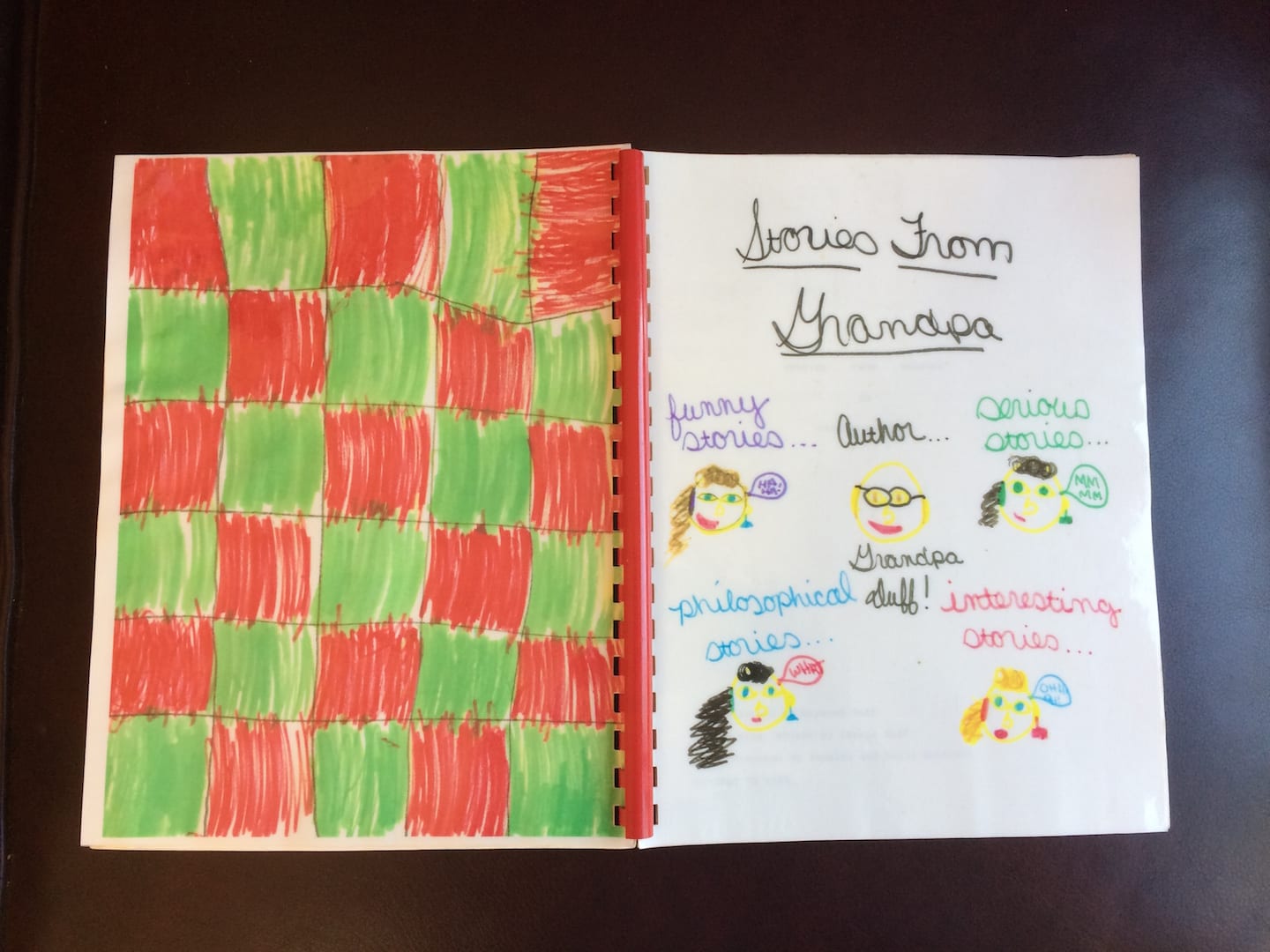

My father told us stories like this when we were growing up, stories with that dry New England humor. During his declining years, he wrote some of these stories for his grandchildren and sent them in letters. We assembled them into a little booklet: Stories From Grandpa. I edited the stories, my daughter drew the front cover, and my son colored the back.

My father told us stories like this when we were growing up, stories with that dry New England humor. During his declining years, he wrote some of these stories for his grandchildren and sent them in letters. We assembled them into a little booklet: Stories From Grandpa. I edited the stories, my daughter drew the front cover, and my son colored the back.

Grandpa wrote about his family history and childhood, about making snow houses in Northern Maine, and about helping his mother hang clothes on the line and solving his runny nose problem with a clothespin. He learned that horses can’t drive through all snowdrifts and that tying together the tails of two wayward cows can result in one less tail.

But the tale I liked the best was about how my parents met. Because Mother grew up on a farm across the road from the farm where my father’s mother grew up, my parents got to know one another well. My father wrote about my mother, “I loved to slide down the hill with her and then walk slowly back so we could talk. I liked her as early as 1930,” when my parents were seven. “”Eventually we fell in love and got married. That is the most wise and important choice of my life.”

It was probably the most wise and important choice of Donald Hall’s great-great-great grandfather’s life, too, all bits of string too short to be saved and memories too important to be thrown away.

What bits of string do you save?

Thanks for this glimpse into another world!

And thanks for visiting and sharing other worlds on your blog.

Thanks, Carole!