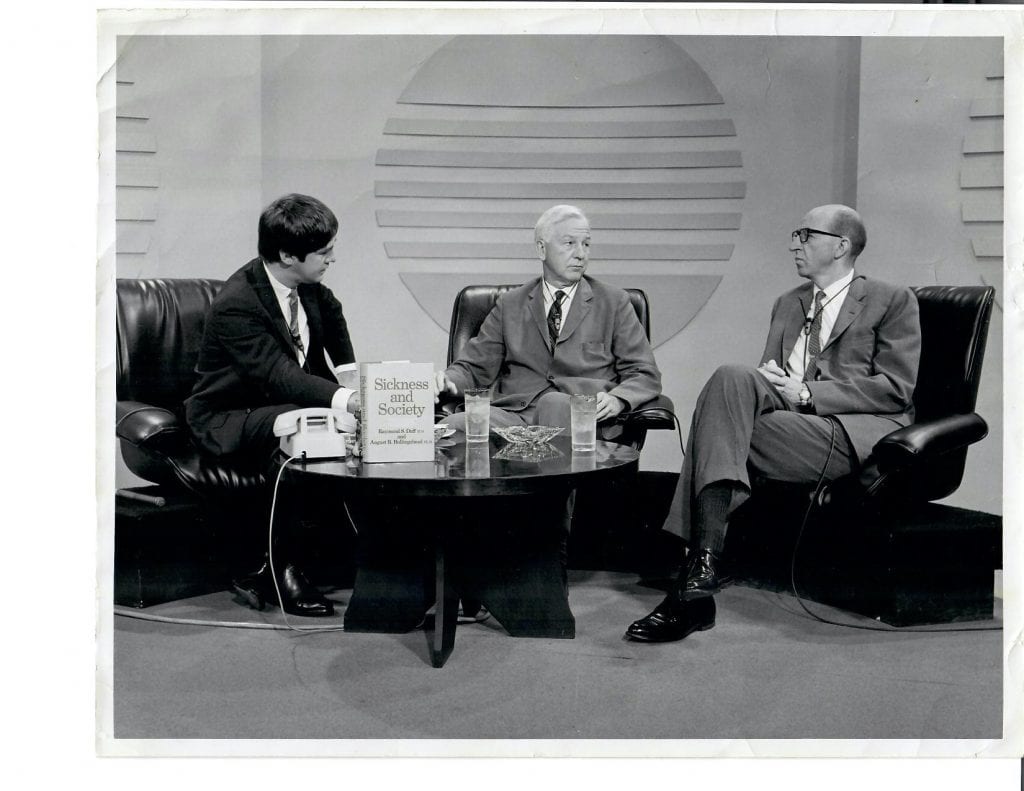

My birth family gathered at the dinner table every night, Daddy at the head across from Mother and we three girls between. Sometimes our father spoke about his work—without divulging confidential information, of course. According to his research with sociologist August B. Hollingshead, people weren’t being cared for as they should in the hospital, and my father and his colleague wanted to change that. Duff and Hollingshead began their study in the early 60s, when I was in grade school. By the time Sickness and Society was published in 1968, I was a full-blow teenager and my father a media celebrity—and less-than appreciated, because he reported the truth.

In our society, human beings do not treat sick human beings very well.

The first time I read my father’s book, I was in high school. No surprise, my understanding filtered through the haze of adolescence. Now, over fifty years later, I decided to re-read his book, to glimpse my father’s work life in his early forties and revisit society in 60s through a more mature heart and mind.

***

The study in the early 60s included 161 families encompassing a range of social classes, from very rich to indigent. To examine the role of spouses in illness, the research sample included only married couples. In general, husbands worked and wives stayed home to take care of household and family.

The hospital in the study was associated with a university medical school and therefore was structured for teaching and research on the university side and for clients of private practice physicians on the community side. Though house staff—residents, interns, and medical students—served throughout the hospital, most of the learning took place in the wards rather than in the semi-private and private room settings for paying customers. Ward patients were viewed as “clinical material,” and most did not seek treatment until they were seriously ill because many were unable to pay. Costs for ward patients were therefore higher, and the financial burden higher, too.

Regardless of social class or hospital setting, Duff and Hollingshead found universal evasion, even deception on the part of physicians and families about illnesses leading to death. Patients were isolated in their dying and subject to hopeless, painful, and expensive treatments so house staff could learn and physicians could hold out hope to families. We’re doing everything possible, they’d say, a cure is just around the corner. House staff told researchers about chilling interactions with the families of dying ward patients to gain permission for autopsies to aid instruction. “I’m sure no New York cop ever beat a confession out of anybody as hard as we beat postmortems out of people sometimes,” one resident said.

Doctors universally focused on the patient’s physical illness, the disease in the body, not the person. As a result, more than a third of the 161 patients were misdiagnosed because personal factors surrounding the illness were ignored. Family dynamics, life history, employment conditions, emotional concerns, such as fear of death or disability, and mental illness were disregarded. Patients also put their faith in physical examinations and laboratory results and did not communicate with doctors.

In the end-of-the-book summary and afterthoughts, Duff and Hollingshead offered the following suggestions: better health insurance programs, the creation of patient advocates within the hospital, and encouragement for patients to express their feelings to physicians in order to receive better care.

Ah, there’s the rub, I thought while reading. How honest are we? How many of us really face the truth about ourselves and our faults, let alone reveal our true selves to others?

***

After Sick and Society, my father focused on improving care in the newborn special care unit, today called the Newborn Intensive Care Unit or NICU, and directed a research study on pediatric practice. One of his colleagues shepherded that book into print after my father’s stroke in 1986. I read Assessing Pediatric Practice in my early forties—my father’s age when Sickness and Society was published—and will re-read his second book this year, too.

I think my father’s work made a difference, given the “focus on the person” experiences I have these days with a large university hospital—different from the one in the research study—and regular solicitation of patient feedback. But we are still human beings. Only by admitting the truth and struggles in ourselves will we be able to treat others well, especially the most vulnerable: the very young and the very sick.

I remember, when we were in grad school, your discussing your father’s work with me. How far we’ve come! Gary and I are both recovering from Covid–doing well, moderate cases–and so grateful for the care we’ve received. Oh my, what a conversation we could have, Carol!

I am so glad to know that you and Gary are recovering well, Cathy, and that you received good care.

I remember you telling me about his books decades ago, so I am so glad you are rereading them at this time of your life. Your article reminds me of my own struggles with endometriosis and 3 surgeries within 5 years. I resented the pat on the head and the patronizing more than the pain of those surgeries. Could not get the truth out of the first doctor! Yes, patients need advocates! Take care!

I remember your story, Pat… exactly what my father’s research documented. Infuriating how we treat one another sometimes, and the terrible consequences. Take good care!

We’ve been very pleased with the care my husband has received before, during, and after his liver transplant, in order to treat liver cancer. Perhaps your father’s book was the reason the medical staff spent time explaining procedures, the reasons behind their choices, etc. One doctor was considering the pros and cons of two different treatments (pre-surgery) and told us, “I’m going to talk with the team before we decide.” Perhaps collaboration in decision-making was part of your father’s study–instead of Lone Rangers making choices on their own! We also were assigned a patient advocate and were asked for feedback after various steps in the process and doctor visits. And we have YOUR father to thank! Thank you, Carole, for sharing about his life’s work.

Oh, Nancy, thank you for much for sharing your story. My father would have been so pleased.

I love the picture of your dad. Thank you for sharing it.

Isn’t it wonderful to have the legacies of our parents? Thank you for sharing yours.

Carole, I appreciate you sharing the background about your father’s research as well as the conclusions. Through his tireless work, he definitely blessed all of us with his legacy.

Thank you, Richard. Although my father has been gone for twenty-five years now, his work continues through others. He would be pleased.